So now you have your ideas all fleshed out so it’s time to get them into a form your collaborators can use. This is your script. As with everything else in this process, there are many ways to do this. This is my way.

4) Writing The Script

I usually start writing the actual script before I finish all the individual page layouts because the book evolves as I script it. I don’t want to be too attached to things further down the road if I get better ideas as I’m writing.

I seem to work best being about two or three sketch pages ahead of my actual script. As I get closer to a page, the rough sketches become much more detailed. I also write in all my dialogue and captions so I can picture how it fits in the panel.

By this time, I usually have found an artist. If you are drawing your own comics and are a decent writer, you have solved the huge problem I face since my art skills are marginal. What are you waiting for? Get to work.

For me, the joy of scriptwriting is like no other thing. I have to be very careful to outline exactly what I expect to be on the page without being so heavy-handed as to stifle the creativity of my artist. I will make it clear about the things I insist on and things I leave to the imagination of my artist.

Here’s my script for page five of the first issue of the Moose comic:

scriptsample

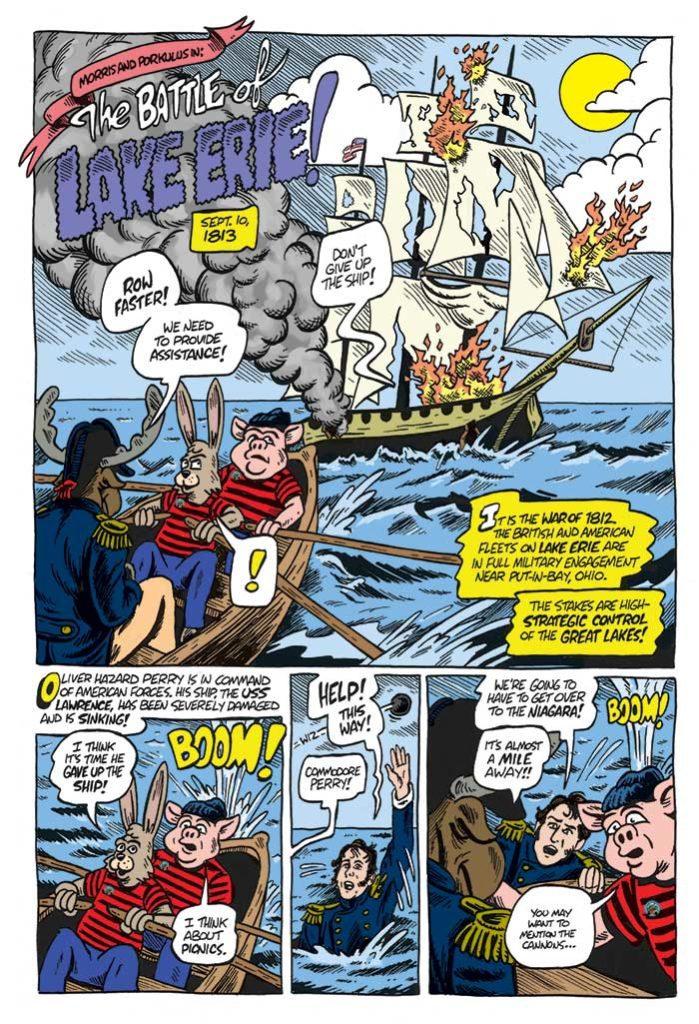

And here’s the final page:

This is a very delicate balance. Comics, like movies, are a collaborative art form. Everybody has strengths they bring to the project. It’s important to recognize those strengths and use them correctly.

At this point, I need to mention one of the rules I always follow as a writer: You must always be ready to kill your darlings. Don’t get so hung up on your own ideas that you are not letting your collaborators use their skills and talents to improve them.

Similarly, don’t be so lazy as to make your artist do all the creative work. There is much more to comic scriptwriting than just writing a bunch of dialogue. Find that balance. It’s hard to do, but the benefits to the project are immeasurable.

As with anything else in comics, there are a bunch of different ways to write scripts. However, there are very specific things which need to be in the script in order for your artist to know what you want. I break down scripts by

1) Page Number.

I identify how many panels I am writing on each page. I think about it as part of a scene, made up of many shots. This is the number of shots on the page.

2) Panel Number.

These are the individual shots, the single moments of action working in a progression to build a scene.

3) Panel overview description.

This includes all the details of the shot and an explanation of what the characters are doing and what is motivating them (if needed).

4) Dialogue.

Each character, sound effect, caption, whatever, is individually identified. The order on the page is generally the order I am imagining the word balloons and text boxes to go.

After I have repeated the process for each of the panels on the page, I mark the End of the Page.

I also include several pages with any kind of references I would like the artist to use. Google Images is a lifesaver for this process. In Mickey Moose #2 we portray a tall ship which is damaged in battle. I found images of the exact ship in different configurations, images of battle damaged ships and I found images of uniforms worn by the sailors of those ships.

The final part of the individual page script is a copy of the sketch page I used to develop the idea. This gives the artist something to at least look at. I try to make it clear where my layouts are important and where I am happy for the artist to use his best judgment.

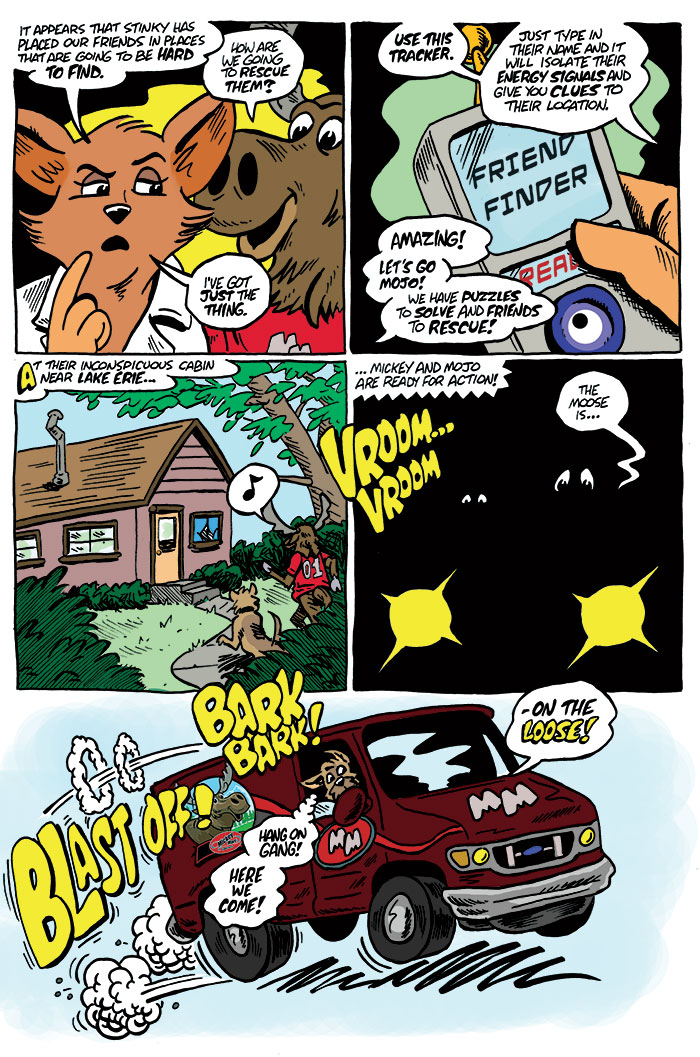

aaomm2p10Aaron never felt comfortable with the way this page was laid out. Several emails were exchanged reworking the script until we were both happy. This is the perfect example of being ready to cut ruthlessly. I was in love with the idea of doing a Looney Tunes tribute with Mickey and Stinky facing off like Bugs Bunny and Yosemite Sam, but Aaron was never thrilled with the idea. He thought it was too confusing and didn’t really move the story forward. In the end, he was right. I think the page works better this way:

Again, this is part of the collaborative process. I know what I’m looking for visually and it helps me easily communicate that to my artist who can concentrate on getting those ideas onto a page.

Leave a Reply